Postcard from a pigeon

Musings by a writer, observer and human citizen on things that make us go...http://dermotthayes.com/dermotthayes.com/The_Story.html

Friday, May 1, 2015

Friday, August 16, 2013

The Lark in the Morning...memories of The Bothy Band

The first time I saw Planxty was in the National Stadium in the early '70s when they played support to Donovan. The first time I saw The Bothy Band was at as lunchtime show in Lecture theatre 'L' in the Arts building in UCD, Belfield. Although there could be no greater contrast in venue; the charged atmosphere of anticipation surrounding the return of a '60s icon like Donovan in the National Stadium on a hot summer evening and the lunchtime lethargy of academia and bored students, vaguely curious to hear a band born from the ashes of a legend, Planxty, that support act from the National Stadium.

I'm not even sure if the name 'Planxty' had been coined before that night in the National Stadium in 1972. To those who knew of him, Christy Moore was the most recognizable figure among the support crew on stage that night, the others were Donal Lunny, Liam Og O'Flynn and Andy Irvine. They only played a handful of tracks, including the Raggle Taggle Gypsy which was to become one of their signature tracks. I went to the show with my brother and he had bought a copy of Prosperous, a 'solo' album recorded by Christy Moore with the same personnel in an old house in his Kildare hometown and, if that album was to be the template for future Planxty albums, that first performance in the National Stadium stamped their authority and presence in the public mind.

Significantly too, Irvine was a former member of Sweeney's Men, an earlier, trailblazing Irish band, cut from the same cloth. Sweeney's Men was a ballad group in the style of The Dubliners and The Clancy Brothers but they derived inspiration and style from further afield that Irish balladry and explored multi-instrumental and non-ballad arrangements that set them apart. Similarly, Donal Lunny had cut his teeth in the folk world with Emmet Spiceland and both he and Moore were boyhood friends. It was Lunny who taught Moore to play guitar and bodhran.

Christy Moore carved out a name for himself on the English folk club scene in the '60s. He hung up his tie and left his bank job during a bank strike and never looked back. With only his guitar and a suitcase, he took the boat to England and cut out a new life and career for himself as a ballad singer. Moore met up with his old pal, Donal Lunny and they brought Andy Irvine and Liam Og O'Flynn together to record Moore's second solo album, Prosperous for what was to become the future blueprint for Planxty.

When Donal Lunny left Planxty in 1973, Dubliner Johnny Moynihan joined the band. Moynihan was another former member of Sweeney's Men and is often credited with introducing the six string bouzouki to Irish folk music.

Liam Og O'Flynn, the fourth member of the original quartet, was a well known solo instrumentalist who had learned his trade at the hands of Seamus Ennis, widely regarded as one of the finest proponents of the uileann pipes, past or present. O'Flynn's distinctive style set Planxty apart and his instrumental tracks, influenced to a large degree by the arrangements of Sean O'Riada, often made up the b-sides of their first single releases.

It was those instrumental leanings that prompted the formation of The Bothy Band by Donal Lunny. The original line up included Paddy Glackin on fiddle, Paddy Keenan on pipes, Matt Molloy on flute, Tony McMahon on button accordion and the brother and sister team of Michael O'Domhnaill and Triona Ni Dhomhnaill. Tony McMahon left to become a producer with BBC and Paddy Glackin was replaced by Donegal fiddler, Tommy Peoples for the band's first album, '1975'. Two more studio albums followed and further personnel changes, most notably, Sligo fiddler, Kevin Burke whose inimitable style became a signature sound. I first heard Kevin Burke play on two tracks of an album by Arlo Guthrie (son of Woody Guthrie) - Last of the Brooklyn Cowboys, 'Farrell O'Gara' and 'Sailor's Bonnet'.

The O'Domhnaills, Michael and Triona, had played together along with their other sister, Maighread in a group called Skara Brae that had often supported Planxty on their tours. They had a wealth of songs they'd learned from a blind, maiden aunt while Michael was an accomplished guitarist and Triona played Clavinet and harpsichord.

There had to be artistic tensions, the fountain of creativity but these, one can only speculate might have been based on more than just musical direction. Planxty and The Bothy Band emerged at a time in Irish history when that Irish cultural identity appeared to have a greater urgency than ever before. In my youth, we listened to The Walton Show on radio when we were admonished/advised that if we felt like singing a song, 'do sing an Irish song' and, ironically, one of that show's most requested songs was Katie Daly, an American folk song.

Planxty, in particular, emerged in the days of internment in Northern Ireland and later, Bloody Sunday, when one of the most popular songs was 'The Men Behind the Wire'. In 1972 John Lennon performed 'The Luck of the Irish', a damning attack on British imperialism's impact on its neighbour and just a year later, Paul McCartney was singing, 'Give Ireland Back to the Irish.' Planxty's songs were noticeably non-political as though they'd made a collective decision to avoid acknowledgement of the very historic events happening on their doorstep that some argued, were the lifeblood of 'folk' music. It's a dilemma, I imagine, that concentrated the mind of Christy Moore in particular and may have prompted or at least, influenced his return to solo work. Indeed, Moore released an album of songs later, that was sold outside the GPO and whose proceeds went to dependents of interned Republicans.

Whatever the circumstances, Planxty and The Bothy Band gave a new generation an introduction to an indigenous culture they could embrace without political baggage.

Of course, there was the other tension, the musical disapproval of their syncopated arrangements led by the so called and self styled 'purists' who tut tutted and 'ciunas'd' their way through every gathering of musicians as though it was their own private club that brooked no changed or embraced any novelty or innovation.

For five years in the '70s I followed these bands and their music and they prompted me to delve deeper into the roots of the tradition that was the core of my own interests but simply hovered like a ghost or an itch I couldn't scratch. Their own leanings drove me to explore music from further afield such as American and British folk, European and African folk and what has, since then, become more fashionably known as 'world music.' But no study or studious collecting could replace the blood soaring excitement of standing in a sweaty marquee in Ballisodare and listening to The Bothy Band let loose with Rip the Calico or that medley of reels, The Salamanca,The Banshee and The Sailor's Bonnet.

Sunday, July 28, 2013

Same Ol' Blues Again...reflections on the death of J.J.Cale

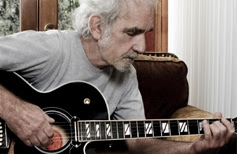

I didn't catch the Sky News report. I heard of the death of J.J. Cale via a text message from my daughter, regretting his passing in deference to my lifelong devotion to the Oklahoman guitarist, the horizontal architect of 'laid back.' I have to say I was shocked, more so than when I heard of the death of Elvis or, indeed, John Lennon. Even Bob Marley.

It was an ex-girlfriend who first tuned me in to him. She had gone looking for the writer of 'After Midnight' shortly after it became a hit for Eric Clapton in 1970. Ironically, Cale himself first learned of Clapton's hit when he heard it playing on the radio of his truck. He was a poor, jobbing musician and delighted to make some money, at last. He made 'Naturally', his first album, in 1971, inspired by the success of After Midnight.

That album's opening track was 'Call Me the Breeze' which was subsequently recorded by Lynyrd Skynyrd, and launched Cale on a path to relative material comfort,as a successful songwriter, after a life of struggle.

I saw J.J.Cale once. It was in the National Stadium on the South Circular Road, in 1977. It was my 21 st birthday celebration, too. We bought 14 consecutive tickets, an entire row, four rows back from front stage.

Back then, the National Boxing Stadium was the primary venue in the country where one night you might see The Chieftains or The Bothy Band and on any another, Van Morrison, Lou Reed, Black Sabbath or even blues' legends like Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, B.B. King or Canned Heat. I know, because I attended those shows around that time, too. It's funny how the term 'eclectic' became fashionable in the '90s as a hip catchphrase for someone's musical interests when, in those days, good music was good music, same as today and same as always.

The 'Stadium, that night, was engulfed in a warm, cloud of pungent smoke from bongs, pipes and spliffs as scruffily attired and tatted roadies with pony tails and prominent ass cracks scurried about the stage, adjusting lights, reassembling cables and wiring, tapping mikes and muttering, 'One - TWO, ONE - two,' in a blur of apparently frenetic activity and beneath the glare of the 'Stadium's houselights.

It was just about then a bedenimmed figure emerged from the dimly lit backstage area and picked his way through the chaos, to the lead mike. This man had grey, curly hair and wore sunglasses but in his denim jacket and jeans, didn't look out of place when he picked up a guitar and began to strum and attune the instrument. Just another roadie, you might've thought, until he launched into the opening chords of 'Call Me the Breeze' and there was an audible, collective, gasp from the audience and, you imagined, from the roadies onstage, as they began to realize the show had started.

The scramble to clear the stage took seconds. Then the lights came down and focussed on the lone figure onstage, his band, only now arriving and strapping in for their own performance. But by then, in his own inimitable style, J.J. Cale was already 'blowin' down the road.'

Last night, I played every album I have of J.J.Cale's and I'm listening to 'Hey Baby', the opening track of Troubadour, his fourth album, as I write this and it sounds as though he was writing his own epitaph, at least, as I'll remember him and always cherish his music.

Hey Baby, you're looking real good,

You make every day a song,

Like I knew you would.'

Saturday, June 8, 2013

PictureHouse and Rod Stewart, a day in the life and a life in a day...

There is a spine chilling feeling you get at a live concert that never happens when you're listening to an artist's album, when all the elements surrounding the event combine, to make that moment 'magic', for want of a better word.

I remember watching Van Morrison as he opened his headlining set with 'Moondance'on the last night of Feile in Semple Stadium, Thurles. A bright, shining, full moon hung in the August summer night above his head. Or the unassuming JJ Cale, when he strode onstage in the National Stadium, unannounced, picked up his guitar and launched into 'They Call Me The Breeze" while harassed roadies scurried about him to complete their tasks. There have been many others that I'll always treasure such as Bob Dylan at Blackbushe, The Clash in TCD and Bob Marley singing 'Natural Mystic' in London's Rainbow Theatre in 1977.

You couldn't recreate it and it can never be bottled, but when it happens, everyone knows.

I got that feeling last night at the PictureHouse show in Vicar St to mark the launch of the band's new album, Evolution and the relaunch of the band for whom the '90s was so full of sparkling, pop promise but who disappeared without trace amid bad decisions, contractual wrangles and changing fashions.

It happened when they sang Heavenly Day, All the Time in the World and Somebody Somewhere and suddenly, the band was playing but the audience was doing the singing. There were young fans in the audience, people who'd come along on the strength of the airplay garnered by Some Night She Will Be Mine but the majority of them were people who first discovered PictureHouse in the '90s and these songs became the soundtrack for their first serious love affairs.

By the time they got to Sunburst, the entire hall was standing, hands aloft and clapping, singing in one voice.

I've experienced the same feeling just occasionally, at a Rod Stewart concert. And it wasn't when the stadium chorus crooned Downtown Train, Sailing or You're In My Heart; no, the hairs on the back of my neck rose with the opening chords of Mandolin Wind or You Wear it Well, both songs written by the tartan terror, himself.

OK, so the latter song sounds suspiciously like another early hit of Rod's, Maggie May but it's still a great song.

Dave Browne of PictureHouse is an incurable romantic; that's his strength. Evolution is aptly named as the songs on this new collection reflect a more worldly, even cautious and experienced approach to life's traffic bumps. But rest assured, Dave's lamp still blazes brightly for lovers.

Rod Stewart's new album is called 'Life' and the opening track, 'She Makes Me Happy' is like a manifesto as he declares the love he's found has saved him. On the second track, 'Can't Stop Me Now', he reflects on how it all started and if you close your eyes, you can visualise that dyed mod mop of hair, sleeves rolled, perma-tanned, tartan clad pop star taking on the world and winning. He tackles divorce, fatherhood, wealth, religion and age.

There's a freewheeling rocker called Beautiful Morning that should have a future as a Top Gear soundtrack or a Goal of the Month compilation.

On both albums, Evolution's Every Step of the Way and Life's Live the Life, a father gives advice to a child.

Rod has always been the lovable rogue, the football loving peacock clown who, you suspect, might have believed his own public image for too long. Now he's writing songs that say, here I am, take it or leave it. There is one song on the album's DeLuxe edition, which boasts three bonus tracks, that sums up this devil may care/fuck you, I'm here attitude. It's called Legless.

"I've been working all my life

trying to make a dollar last

but early this morning

my telephone rang

as I was putting out the trash

It said Excuse me, sir, are you Mr Jones?

I said, yes, I certainly am

He said Congratulations, sir, you're a lottery winner

you're a rich man the rest of your life

chorus

I'm in the mood, I'm in the mood,

I'm in the mood to get legless tonight

I'm in the mood, I'm in the mood to get loaded tonight etc

You think it's classic, Rod Stewart and you want to say, Cheers, Rod because with Life, I think you've hit a creative lottery jackpot. I like both these albums even if both are presented in a style to which I would not, as a general rule, hitch my wagon but what the hell? Rules, be damned, they make me smile.

Saturday, December 22, 2012

Fairy tale of New York in Glasgow

Watching The Story of A Fairytale of New York on BBC2 tonight brought me back to the band's last night of a week of shows in Barrowlands, Glasgow, when they heard the song had reached no 2 in the charts. It was December 23 and the last night of a week of sell out shows. The Pogues were at their peak with a song we all knew, was a thousand times better than The Pet Shop Boys' version of 'Always on my Mind' that pipped them for the Christmas hit. But the news of their being eclipsed didn't dampen their spirits. On the day of that final show, we attended the baptism of Pogues' manager, Frank Murray's children before heading

To see Glasgow Celtic play Aberdeen in a home game. There was, as you might imagine, a fair amount of refreshments consumed. And it continued through the show that night. The last show of a tour, the end of five hectic nights in Barrowlands, the final act in a quest to mark their place among the best in the world; second place disappointed, but didn't dampen their spirits.

We piled on the bus after five encores and headed for The Holiday Inn where the party continued. It was topped off that night when Shane took to the baby grand piano in the foyer of the hotel and, joined by Kirsty McColl, they sang the song. And we all sang it with them. And we cried and laughed and cheered.

I heard them sing that song many times and in many places and, though it remains my favourite Christmas song of all times, it will never be as good as that night.

To see Glasgow Celtic play Aberdeen in a home game. There was, as you might imagine, a fair amount of refreshments consumed. And it continued through the show that night. The last show of a tour, the end of five hectic nights in Barrowlands, the final act in a quest to mark their place among the best in the world; second place disappointed, but didn't dampen their spirits.

We piled on the bus after five encores and headed for The Holiday Inn where the party continued. It was topped off that night when Shane took to the baby grand piano in the foyer of the hotel and, joined by Kirsty McColl, they sang the song. And we all sang it with them. And we cried and laughed and cheered.

I heard them sing that song many times and in many places and, though it remains my favourite Christmas song of all times, it will never be as good as that night.

Friday, October 19, 2012

Reggae Music making me feel good now

After a night filled with the sounds and images from the lives of two legends of 20th century music, Woody Guthrie and Roy Orbison, it's inspired an exploration of the music that soundtracks my life but particularly, the influence of reggae.

The progression from Woody Guthrie or Roy Orbison to reggae might seem quite a leap, musically at least. But then both Guthrie and Orbison came from grassroots folk traditions; country music in the case of Orbison and folk music for Guthrie. Both, in turn, fashioned their own, unique style and voice from those foundations.

Reggae music came from a dancehall culture and the ability of Jamaican musicians to fashion their own versions of the American rock and roll, country and Gospel music they picked up from US radio broadcasts in the '50s and '60s.

Two of my favourite reggae versions of classic songs are John Holt's version of Kris Kristofferson's 'Help Me Make it Through the Night' or Toots and the Maytals version of John Denver's 'Country Roads.' But if you dig around, you'll find reggae versions of anything and everything, including Beatles' songs.

My first memory of hearing and seeing reggae performed was watching Millie Small sing 'My Boy Lollipop' on Top of the Pops. That was in 1964, about a year after I'd first seen The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, my two all time favourite bands. Millie's voice was quite shrill and almost childlike, immediately appealing to an impressionable 8 year old but it was the irrepressible dance rhythm that won my heart.

It would be another four or five years before I encountered reggae and this was with the birth of the skinhead movement in England. Now the irony of why a white and racist gang movement from England should champion a musical style from the Caribbean has always confounded me but at least they put reggae back in my consciousness. Songs and artists from this period - the late '60s and early '70s - that stand out for me, are Desmond Dekker with 'The Israelites' and Max Romeo's banned 'Wet Dream.' Then came Bob Andy and Marcia Griffith's cover of an Aretha Franklin song, 'Young, Gifted and Black' that rose to 11 in the charts in 1971 and Derrick Harriot's version of Pete Wingfield's 'Eighteen with a Bullet.'

But it wasn't until 1973 when I first encountered Bob Marley and The Wailers. I was working in a pub in Paddington at the time and on a day off, I took a stroll up to Portobello Road to browse the market stalls. Back then, Notting Hill had a thriving West Indian community and the walk from Praed St to Portobello brought you right through the heart of it. I remember hearing 'No Woman, No Cry', everywhere and I became obsessed by it. My only regret since then is that I missed out on a chance that summer to witness Marley's first shows in London. I did manage to catch the groundbreaking 'The Harder they Come', the first Jamaican reggae movie starring Jimmy Cliff, in a small cinema in Notting Hill and believe me, it was an awakening for a whole raft of reasons.

The following year I landed a copy of Natty Dread, the first album released as Bob Marley and The Wailers. I remember pouring over that album with my friends, a packet of Rizla and a bag of 'erb.

That summer I was working in Denver, Colorado and decided to hitch hike to New York to hook up with my mates from the UCD Freshman football team for a brief tour of New England. On the road I couldn't escape Eric Clapton's version of 'I Shot the Sheriff' which was being played off the air on FM radio stations, coast to coast. Reggae had suddenly hit the big time.

When I got home I discovered the original version of 'I Shot the Sheriff' on Burnin' by The Wailers, released in 1973. It only fuelled my thirst for reggae and the music of Marley and his companions. Soon I had Catch a Fire, the original vinyl version which I own to this day with it's gimmicky Zippo lighter cover. Two years later the band released Rastaman Vibration. But before that I was in London again, working in The Hog in the Pound on Oxford St where I got to know a Jamaican born dancer named Sylvia who danced topless in the basement bar, two nights a week. Sylvia brought me to Jamaican speakeasies and yard parties in Notting Hill where my love and appreciation of reggae music and the culture that surrounded it, blossomed and expanded.

The progression from Woody Guthrie or Roy Orbison to reggae might seem quite a leap, musically at least. But then both Guthrie and Orbison came from grassroots folk traditions; country music in the case of Orbison and folk music for Guthrie. Both, in turn, fashioned their own, unique style and voice from those foundations.

Reggae music came from a dancehall culture and the ability of Jamaican musicians to fashion their own versions of the American rock and roll, country and Gospel music they picked up from US radio broadcasts in the '50s and '60s.

Two of my favourite reggae versions of classic songs are John Holt's version of Kris Kristofferson's 'Help Me Make it Through the Night' or Toots and the Maytals version of John Denver's 'Country Roads.' But if you dig around, you'll find reggae versions of anything and everything, including Beatles' songs.

My first memory of hearing and seeing reggae performed was watching Millie Small sing 'My Boy Lollipop' on Top of the Pops. That was in 1964, about a year after I'd first seen The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, my two all time favourite bands. Millie's voice was quite shrill and almost childlike, immediately appealing to an impressionable 8 year old but it was the irrepressible dance rhythm that won my heart.

It would be another four or five years before I encountered reggae and this was with the birth of the skinhead movement in England. Now the irony of why a white and racist gang movement from England should champion a musical style from the Caribbean has always confounded me but at least they put reggae back in my consciousness. Songs and artists from this period - the late '60s and early '70s - that stand out for me, are Desmond Dekker with 'The Israelites' and Max Romeo's banned 'Wet Dream.' Then came Bob Andy and Marcia Griffith's cover of an Aretha Franklin song, 'Young, Gifted and Black' that rose to 11 in the charts in 1971 and Derrick Harriot's version of Pete Wingfield's 'Eighteen with a Bullet.'

But it wasn't until 1973 when I first encountered Bob Marley and The Wailers. I was working in a pub in Paddington at the time and on a day off, I took a stroll up to Portobello Road to browse the market stalls. Back then, Notting Hill had a thriving West Indian community and the walk from Praed St to Portobello brought you right through the heart of it. I remember hearing 'No Woman, No Cry', everywhere and I became obsessed by it. My only regret since then is that I missed out on a chance that summer to witness Marley's first shows in London. I did manage to catch the groundbreaking 'The Harder they Come', the first Jamaican reggae movie starring Jimmy Cliff, in a small cinema in Notting Hill and believe me, it was an awakening for a whole raft of reasons.

The following year I landed a copy of Natty Dread, the first album released as Bob Marley and The Wailers. I remember pouring over that album with my friends, a packet of Rizla and a bag of 'erb.

That summer I was working in Denver, Colorado and decided to hitch hike to New York to hook up with my mates from the UCD Freshman football team for a brief tour of New England. On the road I couldn't escape Eric Clapton's version of 'I Shot the Sheriff' which was being played off the air on FM radio stations, coast to coast. Reggae had suddenly hit the big time.

When I got home I discovered the original version of 'I Shot the Sheriff' on Burnin' by The Wailers, released in 1973. It only fuelled my thirst for reggae and the music of Marley and his companions. Soon I had Catch a Fire, the original vinyl version which I own to this day with it's gimmicky Zippo lighter cover. Two years later the band released Rastaman Vibration. But before that I was in London again, working in The Hog in the Pound on Oxford St where I got to know a Jamaican born dancer named Sylvia who danced topless in the basement bar, two nights a week. Sylvia brought me to Jamaican speakeasies and yard parties in Notting Hill where my love and appreciation of reggae music and the culture that surrounded it, blossomed and expanded.

After that there was no stopping. I bought albums by u Roy and I Roy, Dillinger, Culture, Max Romeo, The Upsetters, The Heptones and The Abyssinians and countless others. Soon, I could discern ska from rock steady and dub from dancehall. I bought a single by a band called Dirty Work from Belfast, a reggae version of The Rose of Tralee. Then The Stones released Goat's Head Soup, recorded in Jamaica and I took that as a sign. When they followed that with Black and Blue, I knew I was on the right track. Meanwhile, The Wailers' split up after Rastaman Vibration with Bunny Livingston retreating to his Roots and Peter Tosh became more militant. I bought their solo albums and admired The Stones' patronage of my heroes but the real magic lay in Bob. When the first shows were announced for the tour to launch Exodus, I knew I'd be there.

The show was in the old Rainbow Theatre, near Finsbury Park. I met a friend from Belfast the day before the show. We'd met a few months earlier at a Desmond Dekker show in a small club in Dublin, attended by reggae fans and a large group of, by now paunchy and nostalgic, skinheads and suedeheads. Peadar was from Andersonstown and spoke with his own unique accent that was a peculiar blend of Jamaican patois and West Belfast twang. There wasn't a political bone in Peadar's body but he couldn't escape where he came from. He called it 'Babylon' and we both understood what he meant. All he cared about was the music and the two eight foot high cannabis plants he'd grown and nurtured from seed in the back garden of his parents' house in A'town. He was looking forward to going home to harvest. But first, the concert.

The previous eight months had its hardships for Bob Marley, too. The split with his old mates, Bunny Wailer and Peter Tosh, was, by all accounts, acrimonious. Bob had also become entangled in Jamaican domestic politics and he received a near fatal wounding when his Kingston compound was shot up by a rival political gang. He moved to England to record Exodus. Jamaica's loss was the world's gain.

Denim work overalls were a fashion de rigeur in those days, if you were a slave of hippy fashion and not a punk. They were baggy and comfortable and extremely useful for carrying your stash at a concert. Back in those days you could smoke indoors, even in a theatre so before we marched off to the show, we got rolling. I managed to squeeze half a dozen spliffs into the pen and tool pockets, chest height, on my overalls. But when we got to the show, we found the London Met surrounding the theatre in an over the top security response. There was no trouble but when we got to the door, the theatre's security staff were conducting body searches. The 6'4" Jamaican bouncer who patted me down, stopped on my breast pockets to enquire what I had in size. 'Spliffs,' I said. "That's cool, mon," he said with a smile, "we're only searchin' for weapon."

Although the number of white people at the show could fit in a phone booth, there was no trouble and Peadar and I were pleased to find our seat allocation put us in the fourth row, front and centre. The atmosphere of anticipation was electric. And no-one was disappointed. Marley danced onstage in blue denim shirt and matching trousers and for the next two hours he never stood still as, fired by the ground bass sound of Aston 'Family Man' Barrett, the vocal back up of the I Threes and the artful lead guitar work of Junior Murvin, he delivered a master class in reggae music.

Exodus was anticipated to be an opportunity for Marley to rant against the oppression of the political chicanery and thuggery that made him an exile. Instead, it became an international battle cry for reggae music and a paean to peace and love, too. They sang all the classics like No Woman, No Cry, I Shot the Sheriff and a stomping version of Peter Tosh's Get Up, Stand Up but it was the new songs that entranced, thrilled and won over the adoring audience from the title track, Exodus to the pastoral glory of Three Little Birds and the loving lullaby of Waiting in Vain and then the exploratory rootsiness of Natural Mystic and the final statement of One Love, a declaration of intent and purpose.

Four years later, I caught Bob Marley again. This time it was for one of his final shows in Dalymount Park. He was dying of cancer but just as before, he never stopped moving for the show's near two hour length.

In the preceding punk years, Marley brought reggae to a world audience and the music itself blossomed and found new protagonists such as Steel Pulse, Black Uhuru, Aswad and even UB40. The nascent Two Tone movement found its roots in ska through The Specials, The Selecter and The Beat and even punk found inspiration in reggae through, most notably The Clash's recording of Junior Murvin's Police and Thieves and the very obvious influence infused in many of their songs from London Calling and the heavy dub tracks of Sandinista. Punk and Reggae teamed up for many memorable shows in the Rock against Racism movement.

Thirty years later, Jimmy Cliff has brought it all full circle with an incredible interpretation of The Clash's Guns of Brixton on his 2012 release, Rebirth.

In the intervening years reggae has become an international musical dialect, employed with alacrity and enthusiasm by artists throughout the world. And Jimmy Cliff, a man who was in there at the very beginning, is the appropriate spokesman for its long journey through the years. In the song, Reggae Music, he claims his position with the track's spoken opening lines, 'In 1962 in Kingston, Jamaica, I sang my song for Mr Leslie Kong, he said, let's go record it in the style of ska...' and then the chorus, 'Reggae Music gonna make me feel good, reggae music gonna make me feel alright now...'

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=boPCNaFPrso

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfui3DjgfrM&feature=related

Tuesday, October 16, 2012

Hats

Does anyone know about men's hats in Ireland anymore? Back in the day, buying a hat was easy.

I started wearing my hat, a grey, snap brim trilby, in 1995. I remember the day and the circumstances. The editor of the Evening Herald had just rung me and confirmed my appointment as the paper's diarist, writing a daily column about the city and its denizens and what they got up to of an evening. He asked me to report for duty that day and have my photograph taken for the column's masthead.

Since I'd already spent the previous two weeks writing the column under a self styled pseudonym, 'John Newman', I was familiar with Independent House on Abbey St so when I got there, I went straight up to the photographers' studio at the top of the building. The snapper on duty told me it would only take a minute and he went about fiddling with the lighting and setting up the profile shot. Then I got a flash.

I had just finished reading and reviewing Neal Gabler's 'Walter Winchell: Gossip, Power and the Culture of Celebrity', a biography of an American journalist who, it is widely claimed, was the first gossip columnist. Sweet Smell of Success, an American noir classic starring Burt Lancaster and Tony Curtis and which was loosely based on Winchell, had long been safely ensconced in my Top Ten List of favourite movies.

'Can you wait five minutes?' I asked the snapper, 'there's something I need to do.' Before he answered I was out the door and descending the stairs, two at a time. I ran out the front door and turned left, heading for O'Connell St. I ran across the road and straight in to Clery's department store. Back then, the store had a proper hat department with old men in neat suits and measuring tapes. Quickly scanning the rows and rows of hats in different colours sizes and shapes, my eyes found the hat I wanted. I asked the attendant if I could try one on and he said,'fire ahead' and pointed me to a mirror.

The first hat I tried was too small, the second one, a perfect fit. The attendant stood beside me, attentively. But he took the hat from me and, with a deft and practiced twitch of his wrist, snapped the brim, explaining 'this is a snap brim trilby.' I looked at him in horror. 'Have you another one the same size?' I asked, explaining, 'I don't want the brim snapped.' He sighed and found another hat, unsnapped, and gave it to me, a perfect fit. I paid him and left. In the studio in Independent House, I put on the hat and smiled, 'you can take my picture now.'

The hat achieved all I wanted it to do, and more. I realised, as a diarist, I needed an edge. Winchell worked at night, on the beat of nightclubs, restaurants, theatres and hotel lobbies. I wanted to do the same, to become the eyes and ears of the paper's readers, so when they picked up their paper the next day, they would read an account of the city's social nightlife less than twelve hours after it happened.

I didn't wear my hat on the 'Dublin' side or the 'Kildare' side, as the hatters' and practice believed or advised. I wore it back on my head, unsnapped. I broke the rules but for a purpose. I thought if I wore it too slouched, it might cover my face and give me a sinister or hidden appearance. Wearing it back and unsnapped, left my face open and myself, approachable. It also gave me an identity. People 'knew' who I was when I attended an event and that made it easier for me to approach them. As a journalist, I felt a reluctance to relinquish my anonymity but in the nature of the job I was taking on, it was a necessary sacrifice. My hat got me in doors and that's where the stories were.

It had its ups and downs, of course. As the paper played up my name for finding 'scoops', they played up the association and once advertised three exclusives in the Dairy as 'a hat trick'. Eventually, they changed the name of the diary to 'The Hat.' Me and 'The Hat' were synonymous.

There's a strange thing about hats and public perception of them. Forty years ago and more, almost everyone wore a hat. It was part of your wardrobe, as much as a pair of socks. Then people stopped wearing them. My hat was an exception and for some odd reason, people felt the urge to grab it, steal it, wear it. They never asked and it led me to believe it was an enormous discourtesy, simply bad manners. Yet confronted with their social aberration, one was greeted with blind, incomprehension, as though I was speaking unintelligible gibberish.

On the other hand, as I've said, it got me noticed and it got me in doors. At the black tie opening night of Riverdance in Radio City Music Hall, New York, a leading Irish socialite approached me and introduced me her own gathering of close friends who included the CEO of one of the world's best known insurance companies and the president of a leading international bank. It was a case of mistaken identity. My first clue was how she introduced all her companions to me, indicating I was so famous I didn't require introduction. This was confirmed at the interval when the bank president approached me with his programme in hand and asked me to autograph it for his granddaughter who, he said, was a big fan of my music. I signed it, 'Close to The Edge.'

Another time while I attended the launch of a book about then World F1 champion, Damon Hill in London's impressive Natural History Museum, I was approached by a slouched, grey haired man, wearing a hat and accompanied by three children, I gathered were his grandchildren. 'Excuse me,' he said, 'are you The Edge from U2?' 'No, I'm not,' I told him, adding, 'but right now, I wish I was, Mr Harrison.'

At the gala, star studded opening of Planet Hollywood on St Stephen's Green, the celebrities were coralled in the Conrad Hilton on Earlsfort Terrace before they were transported by waiting limos to the red carpet which began outside the College of Surgeons. Pat Kenny stood on a flat bed truck outside the floodlit entrance of the restaurant and announced the celebrities as they arrived to take the walk down the carpet, cheered by the celebrity spotting public, lining the way. In the Conrad, I was approached by Arnold Schwarzenegger who shook my hand and, leaning close, said, 'I love your hat.'

I shared a limo to the event with singer Michael Ball and his manager. When we emerged from the car, there was a very brief silence before Pat Kenny announced Michael's presence but in that second a local wag could be overheard asking, 'who's dat with The Hat?', prompting Michael to joke it would be the last time he'd give me a lift in Dublin.

The hat could be a nuisance, too and I took to not wearing it when I was on holidays or out with my young, growing family. It could be an unwelcome and frankly, ironic, intrusion.

These days, there's a revival of hats even if everyone opts for that 'porkpie' 'wideboy' look so loved by Hollywood's young and trendy arrivistes. But in Dublin, the real hatters have gone and hats are sold like party treats without any notion of their fashion culture. After buying my first hat in Clery's, someone introduced me to Mr Coyle's shop on Aungier St. It was an old school men's haberdashery where string vests and studded collars could be bought alongside a staggering collection of hats of every shape, size and style. It was a mecca of hats.

Mr Coyle supplied all the hats for the Micheal Collins film and delighted in explaining the subtle differences between a proper bowler and an 'Anthony Eden.' Head to Toe, the RTE fashion show, once approached me to talk about hats and I insisted the interview was done in Mr Coyle's shop. He was delighted. Unfortunately, he was an elderly gentleman and when he died, a great tradition in Dublin died with him.

I started wearing my hat, a grey, snap brim trilby, in 1995. I remember the day and the circumstances. The editor of the Evening Herald had just rung me and confirmed my appointment as the paper's diarist, writing a daily column about the city and its denizens and what they got up to of an evening. He asked me to report for duty that day and have my photograph taken for the column's masthead.

Since I'd already spent the previous two weeks writing the column under a self styled pseudonym, 'John Newman', I was familiar with Independent House on Abbey St so when I got there, I went straight up to the photographers' studio at the top of the building. The snapper on duty told me it would only take a minute and he went about fiddling with the lighting and setting up the profile shot. Then I got a flash.

I had just finished reading and reviewing Neal Gabler's 'Walter Winchell: Gossip, Power and the Culture of Celebrity', a biography of an American journalist who, it is widely claimed, was the first gossip columnist. Sweet Smell of Success, an American noir classic starring Burt Lancaster and Tony Curtis and which was loosely based on Winchell, had long been safely ensconced in my Top Ten List of favourite movies.

'Can you wait five minutes?' I asked the snapper, 'there's something I need to do.' Before he answered I was out the door and descending the stairs, two at a time. I ran out the front door and turned left, heading for O'Connell St. I ran across the road and straight in to Clery's department store. Back then, the store had a proper hat department with old men in neat suits and measuring tapes. Quickly scanning the rows and rows of hats in different colours sizes and shapes, my eyes found the hat I wanted. I asked the attendant if I could try one on and he said,'fire ahead' and pointed me to a mirror.

The first hat I tried was too small, the second one, a perfect fit. The attendant stood beside me, attentively. But he took the hat from me and, with a deft and practiced twitch of his wrist, snapped the brim, explaining 'this is a snap brim trilby.' I looked at him in horror. 'Have you another one the same size?' I asked, explaining, 'I don't want the brim snapped.' He sighed and found another hat, unsnapped, and gave it to me, a perfect fit. I paid him and left. In the studio in Independent House, I put on the hat and smiled, 'you can take my picture now.'

The hat achieved all I wanted it to do, and more. I realised, as a diarist, I needed an edge. Winchell worked at night, on the beat of nightclubs, restaurants, theatres and hotel lobbies. I wanted to do the same, to become the eyes and ears of the paper's readers, so when they picked up their paper the next day, they would read an account of the city's social nightlife less than twelve hours after it happened.

I didn't wear my hat on the 'Dublin' side or the 'Kildare' side, as the hatters' and practice believed or advised. I wore it back on my head, unsnapped. I broke the rules but for a purpose. I thought if I wore it too slouched, it might cover my face and give me a sinister or hidden appearance. Wearing it back and unsnapped, left my face open and myself, approachable. It also gave me an identity. People 'knew' who I was when I attended an event and that made it easier for me to approach them. As a journalist, I felt a reluctance to relinquish my anonymity but in the nature of the job I was taking on, it was a necessary sacrifice. My hat got me in doors and that's where the stories were.

It had its ups and downs, of course. As the paper played up my name for finding 'scoops', they played up the association and once advertised three exclusives in the Dairy as 'a hat trick'. Eventually, they changed the name of the diary to 'The Hat.' Me and 'The Hat' were synonymous.

There's a strange thing about hats and public perception of them. Forty years ago and more, almost everyone wore a hat. It was part of your wardrobe, as much as a pair of socks. Then people stopped wearing them. My hat was an exception and for some odd reason, people felt the urge to grab it, steal it, wear it. They never asked and it led me to believe it was an enormous discourtesy, simply bad manners. Yet confronted with their social aberration, one was greeted with blind, incomprehension, as though I was speaking unintelligible gibberish.

On the other hand, as I've said, it got me noticed and it got me in doors. At the black tie opening night of Riverdance in Radio City Music Hall, New York, a leading Irish socialite approached me and introduced me her own gathering of close friends who included the CEO of one of the world's best known insurance companies and the president of a leading international bank. It was a case of mistaken identity. My first clue was how she introduced all her companions to me, indicating I was so famous I didn't require introduction. This was confirmed at the interval when the bank president approached me with his programme in hand and asked me to autograph it for his granddaughter who, he said, was a big fan of my music. I signed it, 'Close to The Edge.'

Another time while I attended the launch of a book about then World F1 champion, Damon Hill in London's impressive Natural History Museum, I was approached by a slouched, grey haired man, wearing a hat and accompanied by three children, I gathered were his grandchildren. 'Excuse me,' he said, 'are you The Edge from U2?' 'No, I'm not,' I told him, adding, 'but right now, I wish I was, Mr Harrison.'

At the gala, star studded opening of Planet Hollywood on St Stephen's Green, the celebrities were coralled in the Conrad Hilton on Earlsfort Terrace before they were transported by waiting limos to the red carpet which began outside the College of Surgeons. Pat Kenny stood on a flat bed truck outside the floodlit entrance of the restaurant and announced the celebrities as they arrived to take the walk down the carpet, cheered by the celebrity spotting public, lining the way. In the Conrad, I was approached by Arnold Schwarzenegger who shook my hand and, leaning close, said, 'I love your hat.'

I shared a limo to the event with singer Michael Ball and his manager. When we emerged from the car, there was a very brief silence before Pat Kenny announced Michael's presence but in that second a local wag could be overheard asking, 'who's dat with The Hat?', prompting Michael to joke it would be the last time he'd give me a lift in Dublin.

The hat could be a nuisance, too and I took to not wearing it when I was on holidays or out with my young, growing family. It could be an unwelcome and frankly, ironic, intrusion.

These days, there's a revival of hats even if everyone opts for that 'porkpie' 'wideboy' look so loved by Hollywood's young and trendy arrivistes. But in Dublin, the real hatters have gone and hats are sold like party treats without any notion of their fashion culture. After buying my first hat in Clery's, someone introduced me to Mr Coyle's shop on Aungier St. It was an old school men's haberdashery where string vests and studded collars could be bought alongside a staggering collection of hats of every shape, size and style. It was a mecca of hats.

Mr Coyle supplied all the hats for the Micheal Collins film and delighted in explaining the subtle differences between a proper bowler and an 'Anthony Eden.' Head to Toe, the RTE fashion show, once approached me to talk about hats and I insisted the interview was done in Mr Coyle's shop. He was delighted. Unfortunately, he was an elderly gentleman and when he died, a great tradition in Dublin died with him.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)